A Dynamic Analysis of the Neural Latent Space

2025-12-16

Everything we call "self"—our memories, emotions, decisions, and the way we perceive the world—emerges entirely from the physical activity of brain tissue. Understanding how this remarkable organ generates mind from matter stands as one of the most profound challenges in science. Yet a fundamental question remains: how can we systematically analyze the principles underlying brain function and bring cognitive processes into a rigorous mathematical framework?

Traditionally, neuroscientists have analyzed brain states based on signal properties such as power, amplitude, and frequency of neural oscillations. While these approaches have yielded meaningful insights, they rely on relatively low-dimensional measurements that compress neural complexity, losing much information inherent in intricate neural interactions.

Modern neuroscience has begun to overcome these limitations by examining higher-dimensional representations of neural activity. By applying dimensionality reduction, denoising methods, and machine learning techniques to extract salient features and identify consistent trajectories, researchers have discovered structured patterns within these complex data spaces—what we refer to as neural latent dynamics.

In this review, we survey groundbreaking discoveries in neural dynamics across three domains: motor control, sensory processing, and cognitive processes. We further provide an overview of analytical methods used to study neural latent dynamics, offering a foundation for researchers entering this emerging paradigm in neuroscience.

Neural Dynamics of Brain Functions

Dynamics of Motor Control: Motor Cortex as a Dynamical Generator

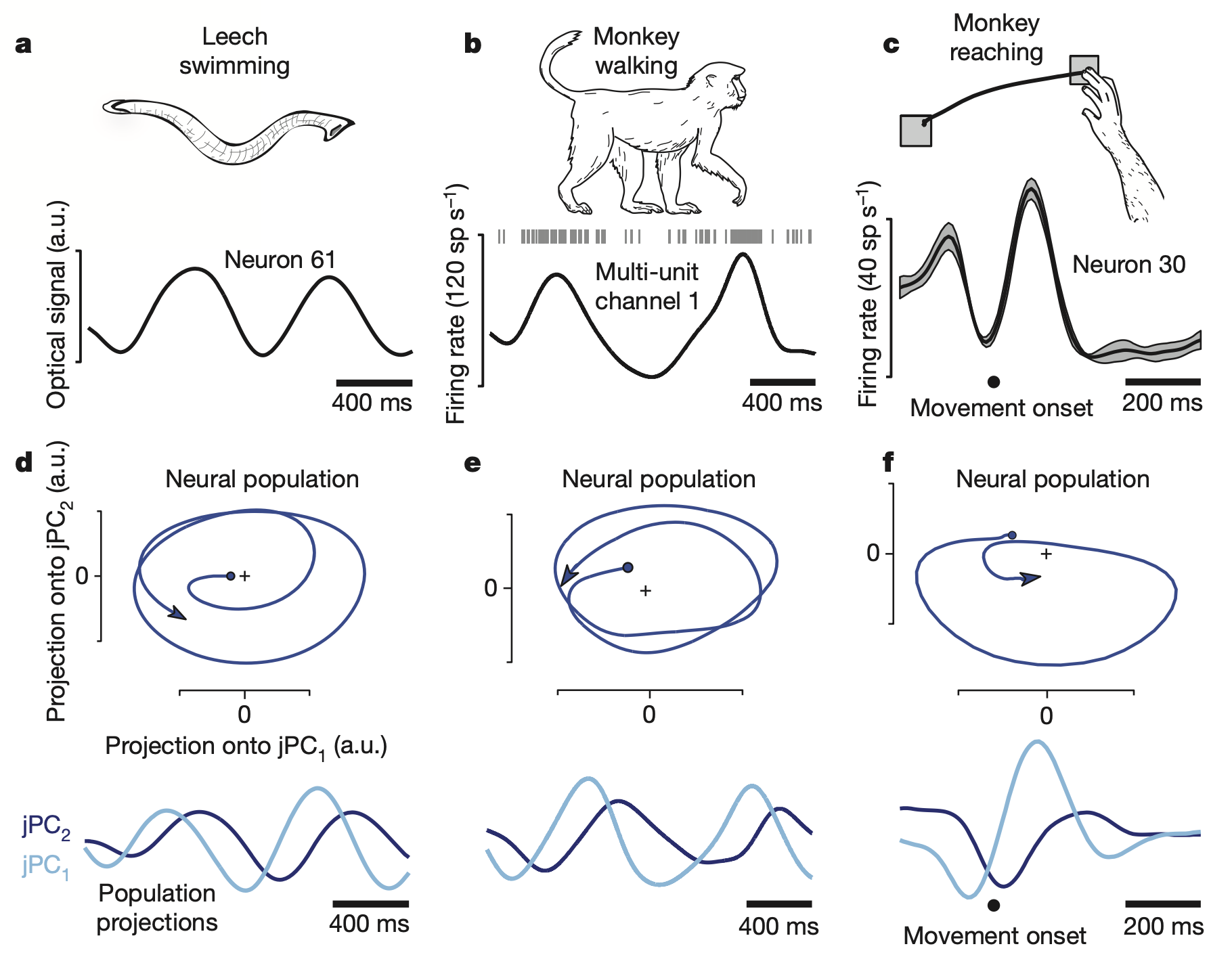

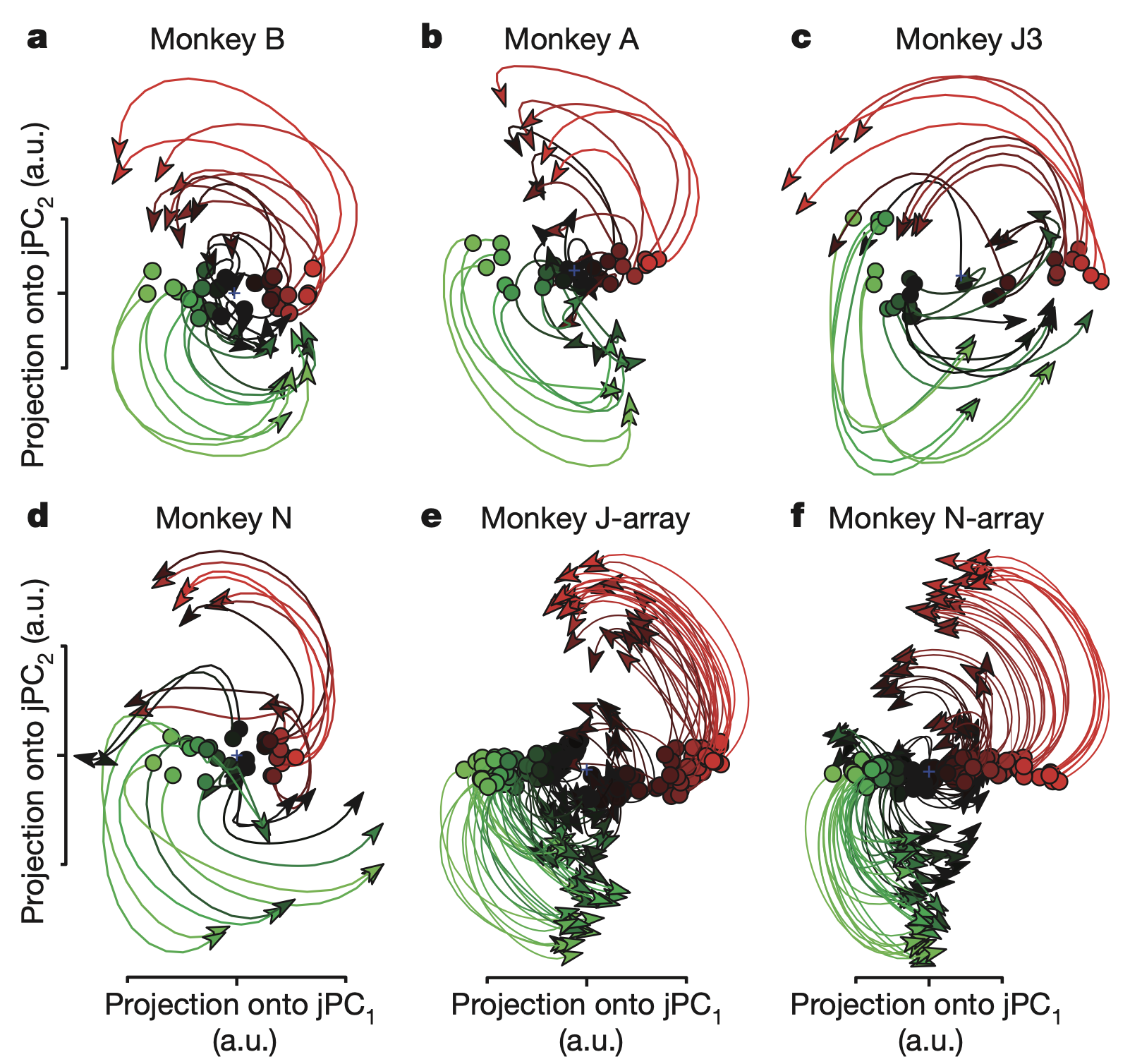

Previous studies have identified rhythmic neural activity during periodic movements such as leech swimming and monkey walking. These findings led to the assumption that neural activity directly encodes movement parameters. However, Churchland et al. (2012) discovered brief but strong oscillatory components in neural responses during non-periodic behaviors such as reaching movements in monkeys.

The researchers recorded from hundreds of neurons in the primary motor cortex (M1) and dorsal premotor cortex (PMd) arm areas of monkeys. And they projected firing rate data onto a two-dimensional latent space using the jPCA technique. This analysis revealed prominent rotational dynamics in the neural state space. A key feature of these dynamics was that the preparatory state served as the initial condition of the system. Specifically, the position of the neural population in state space during the preparatory period—before the go cue—determined the amplitude and phase of the subsequent rotational trajectory.

This rotational structure was consistently observed across all experimental subjects and emerged regardless of whether arm trajectories were straight or curved. More remarkably, these rotations exhibited consistent direction and angular velocity across all movement conditions.

These findings directly challenge the traditional view that neural activity directly encodes movement parameters. This latent dynamics perspective provides a clear explanation for why individual neuron responses appear so complex and multiphasic: the seemingly complex activity of individual neurons is simply the result of reading out this low-dimensional rotational signal through different weighted combinations. Instead, the researchers propose a new perspective in which motor cortex operates as a dynamical system that generates and controls movement, with the observed rotational dynamics representing its intrinsic structure.

Dynamics of Sensory Processing: Transient Trajectories and Fixed Points

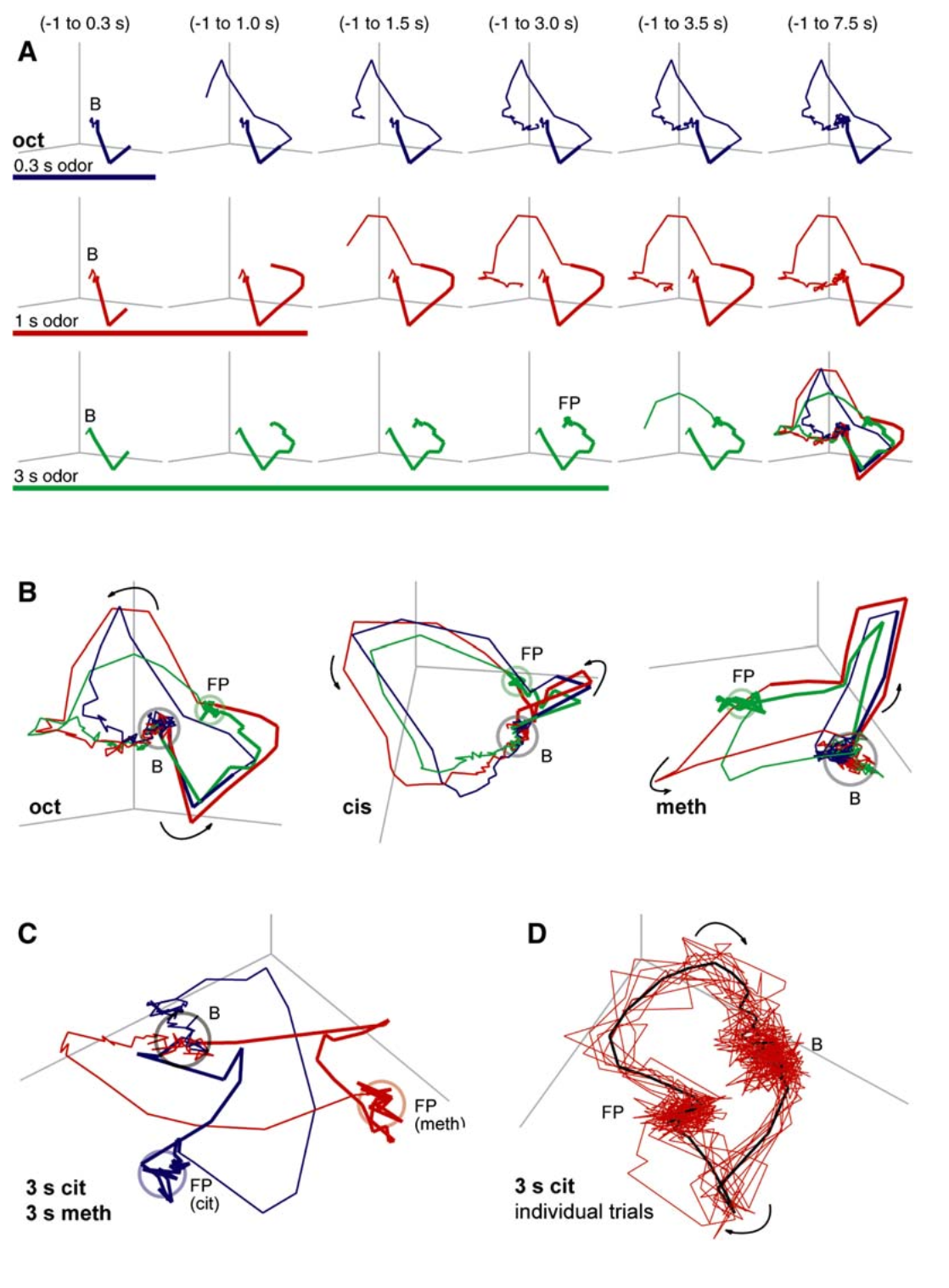

The dynamic nature of sensory information processing is demonstrated in the study by Mazor and Laurent (2005) of the locust olfactory system. The researchers analyzed spike activity from 99 projection neurons (PNs) and discovered that neural population responses to odor stimuli consist of two distinct phases: a transient dynamics phase characterized by rapid changes in firing rates at stimulus onset and offset, and a fixed point phase where firing rates stabilize.

When 99-dimensional PN activity was projected into a three-dimensional latent space via PCA, the fixed point states showed limited capacity to clearly distinguish between chemically similar odors, whereas the transient trajectories achieved clear separation. Specifically, odor discriminability was highest not at the stable fixed points, but during the dynamic trajectories themselves. This occurs because the transient phase maximizes the signal-to-noise ratio: interodor distances (signal) are maximized while trial-to-trial variability (noise) is minimized.

Responses from Kenyon cells (KCs), the downstream target neurons of PNs, suggest that this dynamic coding is not merely a phenomenon but reflects the brain's actual processing mechanism. KCs fired strongly only during the transient phase and became silent when PN activity reached its fixed point. This indicates that subsequent brain stages deliberately ignore information from stable states and selectively decode only the information contained in dynamic moments of change. Therefore, in this sensory system, information is encoded not in fixed states but in the trajectories of neural activity itself.

Dynamics of Cognitive Processes

Spatial Working Memory

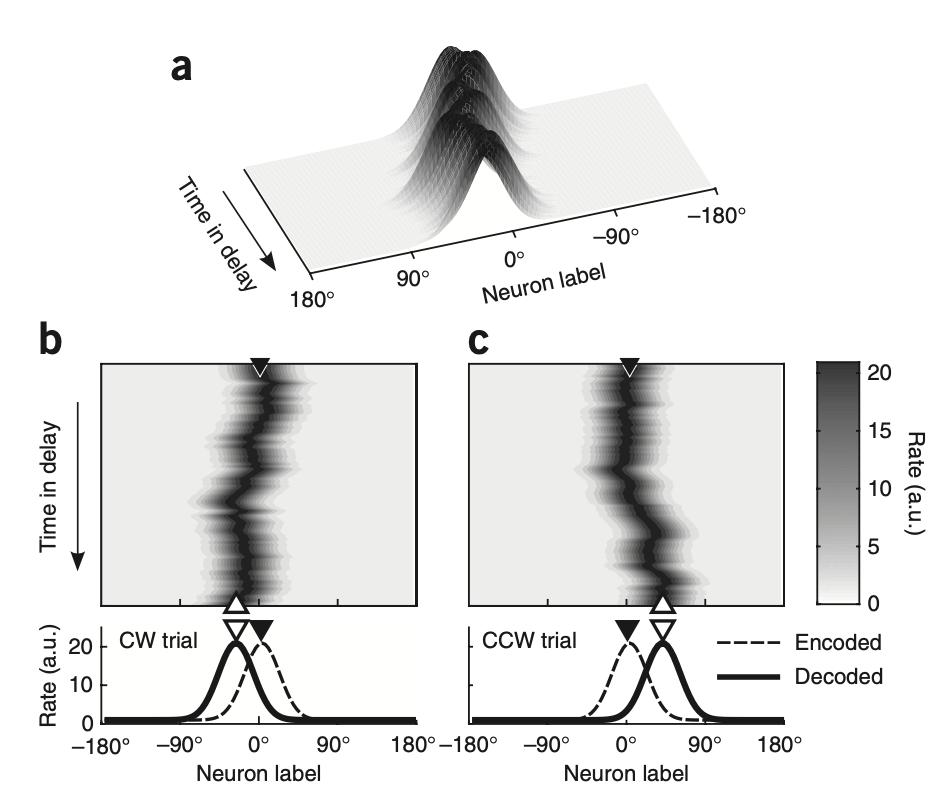

Spatial working memory (SWM) is a cognitive function that actively maintains spatial location information for a period even after visual stimuli have disappeared. Classical studies have identified persistent activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) during SWM as the neural correlate of memory. However, these findings, based primarily on trial-averaging, demonstrate only correlations and fail to explain why memory accuracy varies subtly from trial to trial (imprecision).

The most prominent theoretical model explaining SWM is the bump attractor model. This model posits that memorized location information is stored as a bell-shaped activity bump in the PFC network, and predicts that this bump is not perfectly fixed during the delay period but instead undergoes random drift due to neural noise.

Wimmer et al. (2014) analyzed spike activity from 204 single units recorded in monkey PFC and provided the single-trial demonstration that this theoretical model accounts for actual memory errors. Their key analytical approach was to separate trials based on behavioral errors rather than averaging across all data, and to directly compare neural activity in these subsets against predictions of the bump attractor model.

The critical evidence is as follows:

- When analyzing only trials in which monkeys made memory errors in a specific direction, it was confirmed that PFC neural activity bumps had drifted precisely in the direction where the error occurred during the delay period.

- In trials where a specific neurons firing rate during the delay period was higher than average, the monkeys final memory report (gaze) showed a tendency to be biased toward that neurons preferred location.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that imprecision in SWM is not simply an error but arises from a specific physical phenomenon: random drift of neural dynamics. By establishing this, the study provided strong experimental evidence for the hypothesis that PFC maintains memory through bump attractor dynamics.

Decision Making

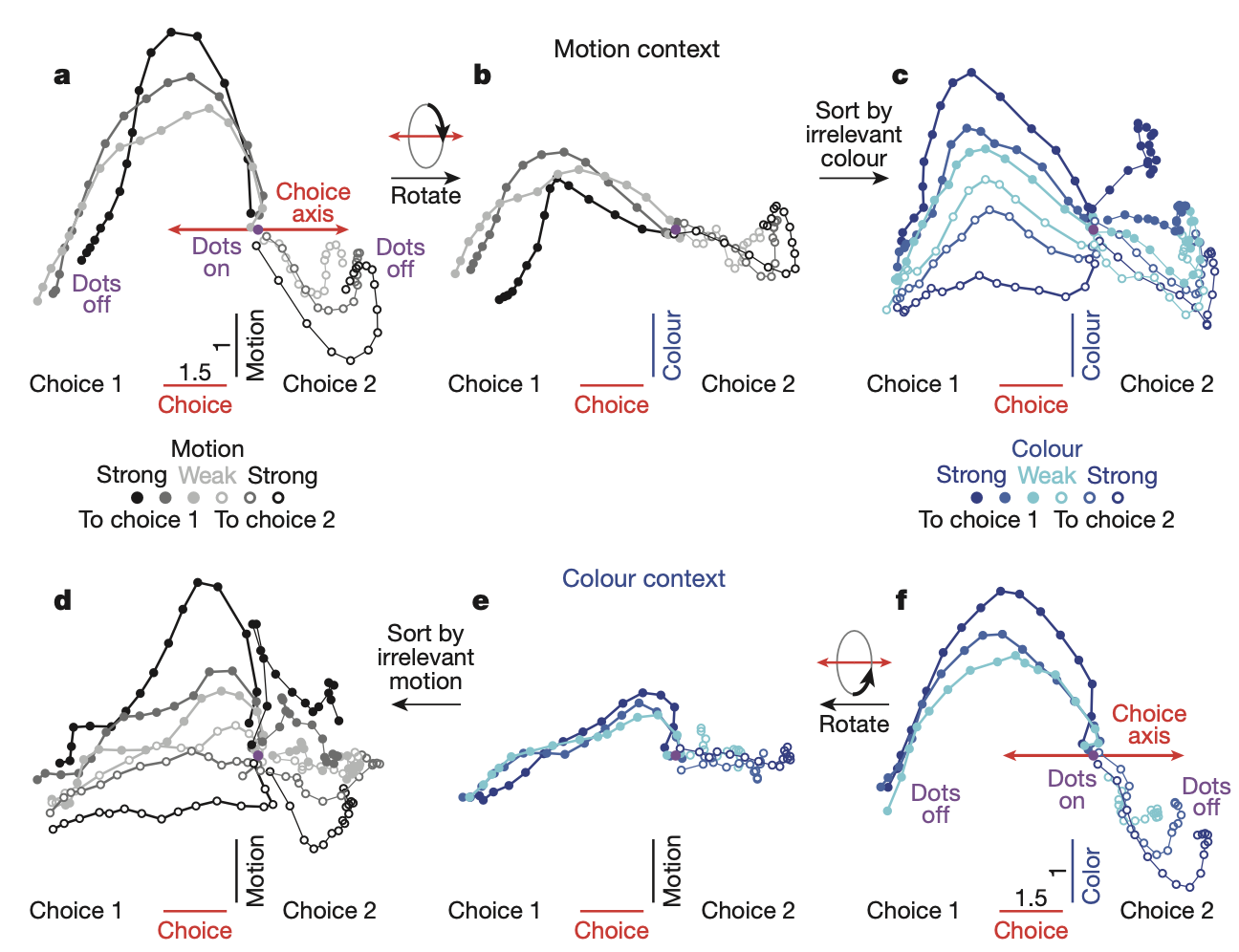

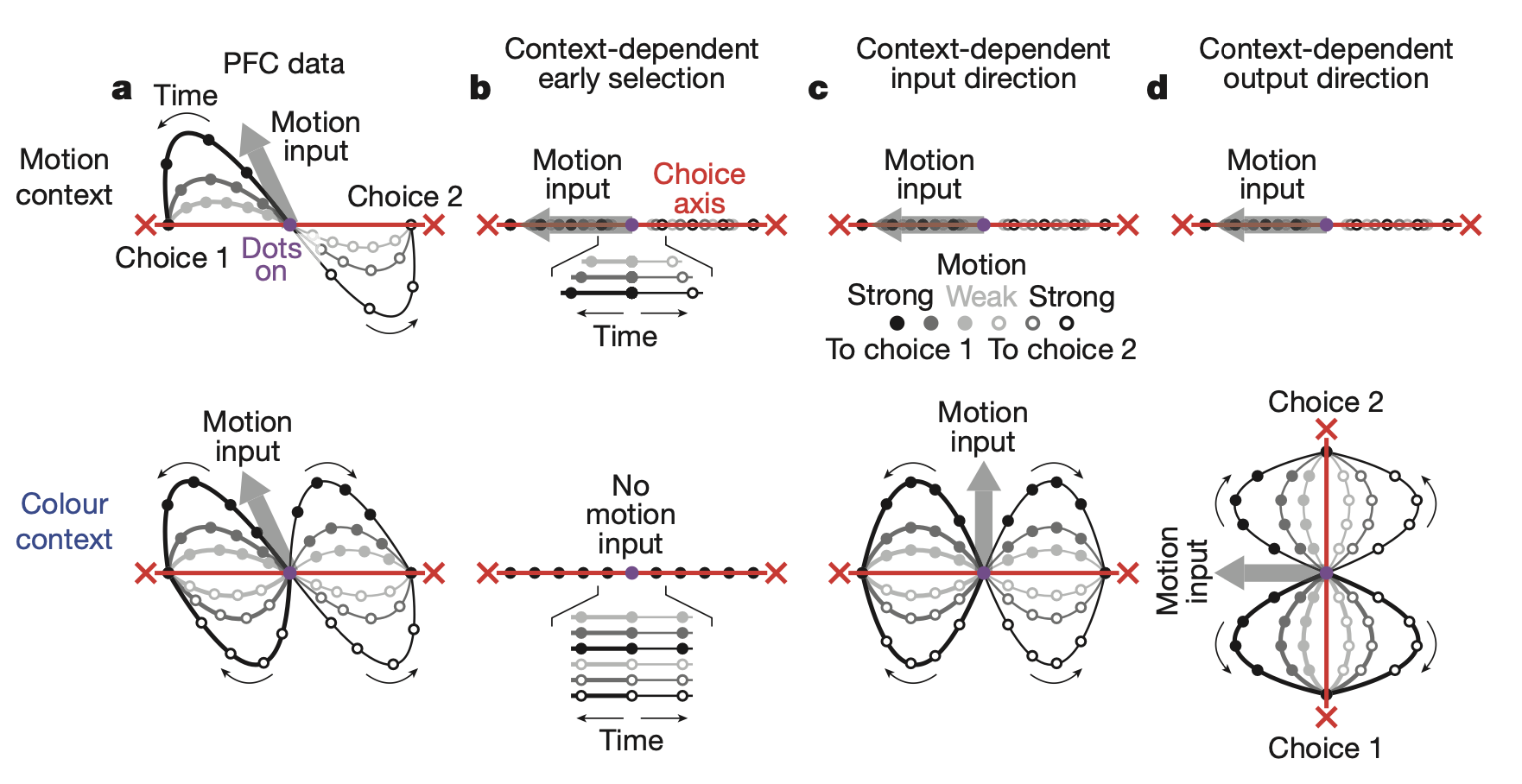

The essence of higher cognitive function is the ability to think flexibly according to context. That is, even when identical sensory inputs are given, entirely different decisions must be made depending on which rule is applied. Mante et al. (2013) elucidated how such flexible computation is implemented through collective dynamics in the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

The researchers trained monkeys to view visual stimuli consisting of random dots and to judge the average direction of dot motion in the motion context or the average color of dots in the color context. In other words, while two types of sensory information (motion and color) were simultaneously presented, depending on the context, one became relevant information and the other became irrelevant information (distractor).

During task performance, spike activity was recorded from a total of 1,402 units (388 single units, 1,014 multi-units) in the monkey's prefrontal cortex (PFC). Individual neuronal activity was highly complex, with multiple types of information (motion, color, context, final choice, etc.) appearing intermingled. However, to analyze population-wide activity, the researchers employed a targeted dimensionality reduction technique combining PCA and linear regression.

Through this analysis, they successfully isolated mutually orthogonal axes in latent space representing four key types of information:

- Choice axis: The monkeys final decision

- Motion axis: Motion information

- Colour axis: Color information

- Context axis: The currently applied rule

In this latent space, the decision-making process manifested as the following dynamics:

- Integration: The process by which the monkey collected evidence to make a decision appeared as a trajectory in which the neural activity state progressively drifted along the choice axis.

- Selection: The brain does not filter irrelevant inputs at the input stage. Both types of information were represented in PFC. Instead, the context signal moved the entire state of the neural network to a completely different region along the context axis.

- Dynamic Gating: When the brain was in the motion context state, the intrinsic dynamics of the network connected only inputs from the motion axis to drift along the choice axis, whereas in the color context state, only inputs from the color axis were connected to the choice axis.

This demonstrated that selection and integration of information are not two separate processes, but rather an integrated process achieved by reconfiguring the dynamical rules themselves within a single dynamical system in PFC according to context.

Methodologies for Latent Dynamic Analysis

PCA, FA

The analysis of neural latent dynamics begins with extracting low-dimensional latent structure from high-dimensional neural population activity data. Two classical linear techniques traditionally employed for this purpose are Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Factor Analysis (FA).

PCA identifies orthogonal axes that maximally explain the total variance in the data. It operates by computing the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the data covariance matrix, selecting the eigenvectors associated with the largest eigenvalues as principal components. This approach is valuable for dimensionality reduction, extracting significant features, and enabling visualization of high-dimensional neural data.

In contrast, FA is a model-based approach that assumes observed data is generated as the sum of shared latent factors and unique variance specific to each neuron. This framework is well-suited for extracting common input signals that underlie population activity, making it conceptually aligned with the goal of identifying shared neural dynamics.

However, these classical techniques possess inherent limitations for analyzing dynamics. Both methods treat each time point as an independent sample, making them fundamentally static approaches. Consequently, PCA and FA cannot model the temporal structure or the flow of trajectories inherent in the data. These limitations have motivated the development of subsequent methods, such as Gaussian Process Factor Analysis (GPFA), which explicitly incorporate temporal structure and enable extraction of single-trial trajectories.

GPFA

Neural activity data are inherently high-dimensional and noisy due to the stochastic nature of spike generation. Traditionally, trial-averaging has been employed to compute mean firing rates, suppressing noise and clarifying signals. However, this averaging process has a critical limitation: it eliminates trial-to-trial variability, which contains essential information for analyzing cognitive tasks such as motor planning and decision-making where internal brain states vary across trials.

This motivated efforts to extract smooth latent trajectories from single-trial data. Early approaches followed a two-stage process: (1) first smoothing data with an arbitrary Gaussian kernel, then (2) applying static dimensionality reduction techniques such as FA to the smoothed data. However, this approach suffers from two key problems: the separation of the two stages prevents joint optimization, and the kernel width () for smoothing must be specified arbitrarily.

To address these limitations, Yu et al. (2009) proposed Gaussian Process Factor Analysis (GPFA), which unifies smoothing and dimensionality reduction within a single probabilistic framework. GPFA combines the Factor Analysis model with a Gaussian Process (GP) as a temporal prior.

1. Observation Model (Factor Analysis): The high-dimensional observed neural activity () is assumed to be generated by a linear transformation () of a low-dimensional latent state (, ).

where represents the spike counts of neurons at time , is the latent state vector, is the factor loadings matrix, and is a diagonal matrix representing the private variance of individual neurons.

2. Dynamics Model (Gaussian Process): The key innovation of GPFA lies in explicitly modeling the temporal structure of . The trajectory of each latent dimension () is assumed to be drawn from a Gaussian process that embodies the smoothness assumption—that states at nearby time points should be similar:

where is a kernel matrix defining the covariance between time points and , containing a timescale parameter () that determines how smoothly evolves over time

GPFA combines these two models to infer smooth latent trajectories that best explain the observed noisy data . GPFA simultaneously learns from the data both the FA parameters (, ) and the timescale parameters that define the degree of smoothness.

Consequently, GPFA extracts single-trial trajectories with data-optimized smoothing without requiring arbitrary kernel width selection. Yu et al. (2009) demonstrated through cross-validation that GPFA consistently achieves lower prediction error than existing two-stage methods.

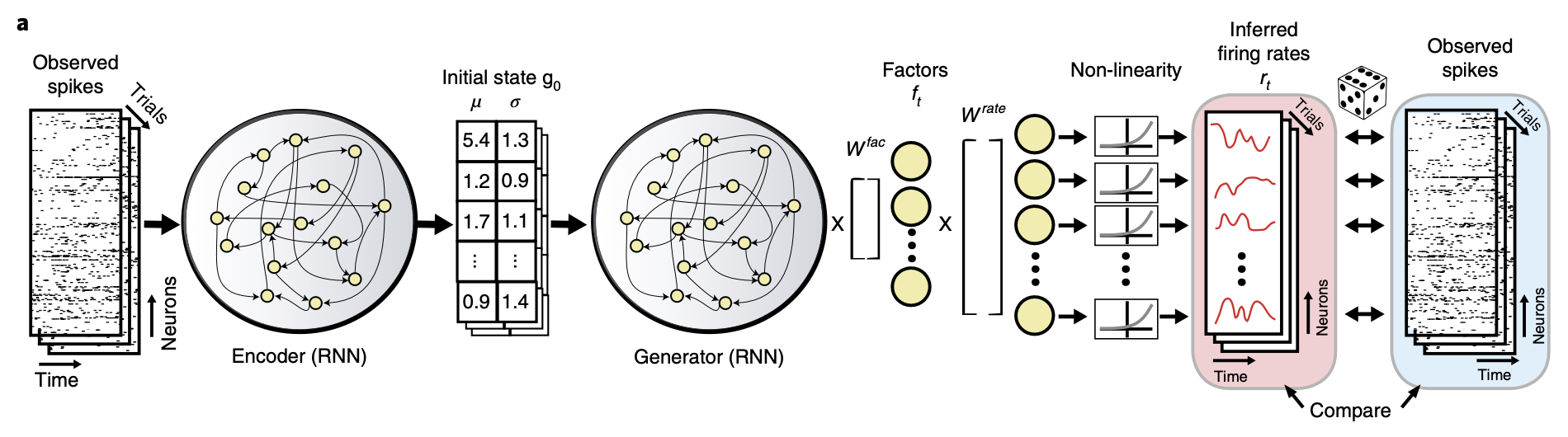

LFADS

Although GPFA elegantly models temporal structure, it is ultimately constrained by an assumption of linear latent dynamics. Neural circuits, however, are inherently complex non-linear systems. LFADS (Latent Factor Analysis via Dynamical Systems) was introduced as a deep learning-based methodology specifically designed to capture these non-linear dynamics (Pandarinath et al., 2018).

LFADS is built upon a sequential autoencoder architecture. The model posits that the high-dimensional observed spike data () are generated from a low-dimensional, non-linear dynamical system:

The mechanism operates in three stages:

- An Encoder RNN bidirectionally processes an entire single-trial spike sequence, compressing it into a single latent code representing that trial's unique initial state ().

- A Generator RNN, which itself embodies the learned non-linear dynamical system, receives this as its initial condition. It then autonomously evolves over time to produce a smooth, low-dimensional latent trajectory ().

- A Decoder maps this latent trajectory back to the high-dimensional neural space, thereby inferring the de-noised firing rates () for each neuron.

The primary strength of LFADS lies in its capacity to effectively de-noise highly stochastic single-trial data. A key demonstration of this power is its success in extracting complex rotational dynamics—phenomena previously only observable through trial-averaging (e.g., Churchland et al., 2012)—at the single-trial level. Furthermore, latent trajectories inferred by LFADS have shown superior performance in decoding behavioral variables compared to those from GPFA.

Discussion

Traditional approaches in neuroscience have largely focused on inferring brain function through meticulously designed external tasks or decoding algorithms, often characterizing neural activity merely as scalar magnitudes of response. In contrast, the studies reviewed here consistently demonstrate a paradigm shift: treating neural activity not as static responses but as dynamical systems described by differential equations of the form . By attempting to analyze these intrinsic dynamics, recent research has successfully elucidated complex phenomena that traditional perspectives failed to capture or reproduce. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the brain requires abandoning the view of it as a static machine for information storage and adopting the perspective of a dynamical machine that transitions its internal states in response to inputs.

Historically, the success of such dynamical analyses was constrained by methodological limitations. In high-noise regimes, the reliance on trial-averaging to extract information paradoxically resulted in the loss of critical trial-specific variability. The finding by Mazor and Laurent (2005)—that the transient phase contains higher discriminability than the stable fixed point—serves as a prime example that the brain utilizes moments of state transition rather than static stability. Fortunately, the rapid advancement of machine learning techniques such as GPFA and LFADS has begun to overcome these hurdles, enabling the effective denoising of data while dramatically preserving single-trial internal states.

However, a significant gap remains: the inability to fully interpret these functions at the level of physical neural circuits. While we have mathematically characterized latent dynamics, the specific synaptic weight configurations that give rise to these rotational trajectories or attractor structures remain elusive. As noted by many experts in artificial intelligence, deep learning models often achieve high task performance without necessarily reflecting the biological architecture of the brain. Consequently, the uncritical application of AI models, such as RNNs or Transformers, to neural activity without biological validation risks yielding distorted intuitions. Ultimately, the goal of neuroscience must remain anchored in a mechanistic understanding at the circuit level.

Conclusion

The methodological framework of constructing mathematical latent spaces and analyzing their internal dynamics is rapidly expanding, driven by a powerful synergy with modern machine learning and deep learning techniques. This review posits that this approach occupies a strategic position, bridging the gap between the understanding of high-level neural computations and low-level neural circuit mechanisms. As our comprehension of the brain as a dynamical system deepens, it is expected to provide not merely descriptive observations, but mechanistic insights essential for interpreting biological circuitry. Ultimately, the rigorous analysis of neural latent dynamics serves as a foundational step toward unraveling the fundamental principles of biological intelligence.

References

- Churchland et al. (2012): Churchland, M. M., Cunningham, J. P., Kaufman, M. T., et al. (2012). Neural population dynamics during reaching. Nature, 487, 51–56.

- Mazor & Laurent (2005): Mazor, O., & Laurent, G. (2005). Transient Dynamics versus Fixed Points in Odor Representations by Locust Antennal Lobe Projection Neurons. Neuron, 48(4), 661–673.

- Wimmer et al. (2014): Wimmer, K., Nykamp, D. Q., Constantinidis, C., et al. (2014). Bump attractor dynamics in prefrontal cortex explains behavioral precision in spatial working memory. Nature Neuroscience, 17(3), 431–439.

- Mante et al. (2013): Mante, V., Sussillo, D., Shenoy, K. V., et al. (2013). Context-dependent computation by recurrent dynamics in prefrontal cortex. Nature, 503, 78–84.

- Yu et al. (2009): Yu, B. M., Cunningham, J. P., Santhanam, G., Ryu, S. I., Shenoy, K. V., & Sahani, M. (2009). Gaussian-process factor analysis for low-dimensional single-trial analysis of neural population activity. Journal of Neurophysiology, 102(1), 614–635.

- Pandarinath et al. (2018): Pandarinath, C., O'Shea, D. J., Collins, J., et al. (2018). Inferring single-trial neural population dynamics using sequential auto-encoders. Nature Methods, 15, 805–815.